The Comfortability Scale

(Originally written 06-16-19; revised and published 01-19-21)

The Comfortability Scale is an attempt to model degrees of trust and vulnerability between people.

Basic Formulation

The scale runs from 0 to 100, with higher values corresponding to higher levels of “comfortability”. We can roughly define comfortability as a measure of how much personal information two people are willing to share with each other. While it’s easy to think of the scale in terms of percent of personal information two people are willing to share, it’s better to have each point correspond to a new “milestone” in sharing.

For example, if two people have 30 comfortability with each other, they are willing to share more with each other than two people at 15 comfortability. Of course, the numbers are arbitrary and there is no good way to precisely define what the difference between a 15 and 20 is, besides that 20 is a little higher than 15. This is beside the point though, as we don’t need such precision.

0 comfortability implies you aren’t willing to share anything with someone. This is extremely rare in practice; maybe someone who refuses to talk to the police, for example, wouldn’t even give them their name, among other things.

100 comfortability implies you’re willing to share everything with someone. We can think of 100 as encompassing everything you know and think about yourself. Excluding severe mental disorders where filters don’t exist, I don’t think in practice this can be achieved by any pair of people, as I explain later.

In between 0 and 100 is where things get interesting. Below are some rough markers giving my idea of various levels of comfortability. Of course, different people will have different thresholds of sharing certain information with others, so again, these numbers are fairly arbitrary and certainly imprecise.

Rough Intermediate Scale Markers

Below 10, you trust someone less than a complete stranger -— maybe they’re a known criminal or seem sketchy for some reason. In cultures with low crime, the default comfortability for strangers would be higher than in a crime-ridden area.

A 10 corresponds roughly to a complete stranger. You are willing to share some basic details like your name or career and place some minor trust in them, but likely not much. While 10 sounds like a very low level of comfort to have even with strangers, I emphasize that this value is not a percentage of total personal information willing to be shared. Each additional point represents an increasingly difficult and rare milestone in the sharing of personal information. As a result, the scale is very skewed towards grouping most people towards the bottom, with numbers higher than 50 or so becoming quite rare.

A 20 could be a decent acquaintance. You know each other and have interacted with each other enough to be at least slightly friendly, perhaps having had a couple short personal conversations. Maybe you are both part of the same organization, but don’t share close ties within it. You are willing to share a little more about yourself.

A 30 is a decent friend, someone you trust a fair amount. They are someone you’ve had conversations with and have spent a decent amount of time with.

40 corresponds to a good friend. You know them pretty well and you guys get along nicely. You place a lot of trust in them and you can share some vulnerable things with them, like fairly deep insecurities or moderately traumatic events. You’ve spent a lot of time with them and feel they have your back.

A 50 is a really good friend. You place a lot of trust in them as you are willing to share some things with them that you find really embarrassing or potentially damaging if word were to get out. You would probably feel quite sad if one of these people left your life; these people can easily turn into lifelong friends if logistics allow. There are still some important or serious aspects of your life that you would be unwilling to share with them, but you’re willing to share a lot more with them than the vast majority of people in your life.

Reaching 60 means a lot and is quite rare. Around here, you might find what I imagine is the upper limit of platonic friendship for many people, and the results of strong long-term romantic relationships. You have a long history with this person and they might know numerous things about you that could be very damaging or catastrophic to your life if certain other people heard (e.g. some crimes you committed, extremely embarrassing aspects of your life, some of your worst or weakest moments, etc.)

The numbers 70 and higher are essentially extensions of 60, representing increasingly difficult levels of trust to achieve. A 70 might be reached for example by a strong married couple that has been together for several years and some serious hardship. An 80 is a step higher —- maybe a couple that has gone through some very difficult or traumatic experiences over a 20 or 30 year marriage but have stuck with each other through thick and thin. These people trust each other with their lives and will almost certainly spend the rest of their lives together.

A 90 is nearly an impossible ideal, but maybe if you’ve spent 60 years together and share essentially every possible aspect of your lives together, then a 90 could be reached. While it seems a bit silly that we’d cap a scale for human interpersonal relationships roughly at 90 — as then what are 91–100 for? — except for only the most extreme cases, I don’t really think two people can be as comfortable with each other as someone can be to themselves. I believe that there will always be some gap, and some thoughts will always be off-limits. Plenty of people might disagree, and this I think isn’t too relevant to the overall discussion for now, but I’ll address it later.

At this point, this concept of the Comfortability Scale might not seem so profound. And maybe, it actually isn’t. However, I think modeling human relationships in this way has some value. When talking with friends familiar with it, it serves as a useful tool for expressing certain ideas.

Clarifications and Extensions

Let’s try to develop this idea a bit further. But first, keep in mind that this scale is not terribly precise, and there are plenty of objections to be made with some of the definitions and chains of reasoning I mentioned above.

What Does Comfortability Represent?

Earlier I said that comfortability roughly corresponds to the amount of personal information you’re willing to share with someone. Well, what makes someone willing to share certain kinds of information and not others? As I will argue in a later article, power and trust are very much involved when we determine what to share with people.

The knowledge of basic information like our names and general appearance generally don’t give much power to others over us, so we usually are fairly comfortable giving those out (though in some cases, like within anonymous criminal networks, this is not the case.)

Embarrassing details and sensitive personal information are potentially more damaging if they enter the public sphere, so we tend to share such topics only with people we trust.

Some things are secrets taken to the grave — serious crimes, affairs, etc. — that people won’t share with even their closest friends and family. If such secrets were to be revealed, they could have devastating legal, social, financial and political consequences, and thus we trust few or no people with such power. Let it be clear that comfortability is determined by what you could comfortably share, and not what you think would be relevant or useful. For example, I have some friends I don’t care to share details of my personal health with. I would be comfortable doing so, but given the nature of our relationship, the topic is not relevant and hence not discussed.

Topics Have Different Comfortability Thresholds For Each Person

I want to emphasize that the topics at each comfort level change depending on the person. For example, if you come from a culture where homosexuality is extremely frowned upon, “coming out” might be something reserved for people at 60 or even higher, while someone who’s lived their entire life in a very liberal Western city might easily share that information with complete strangers. A member of a religious family undergoing a massive change of faith might be very hesitant to share their religious beliefs with others. Meanwhile, plenty of people don’t hesitate to broadcast their beliefs to anyone that walks by.

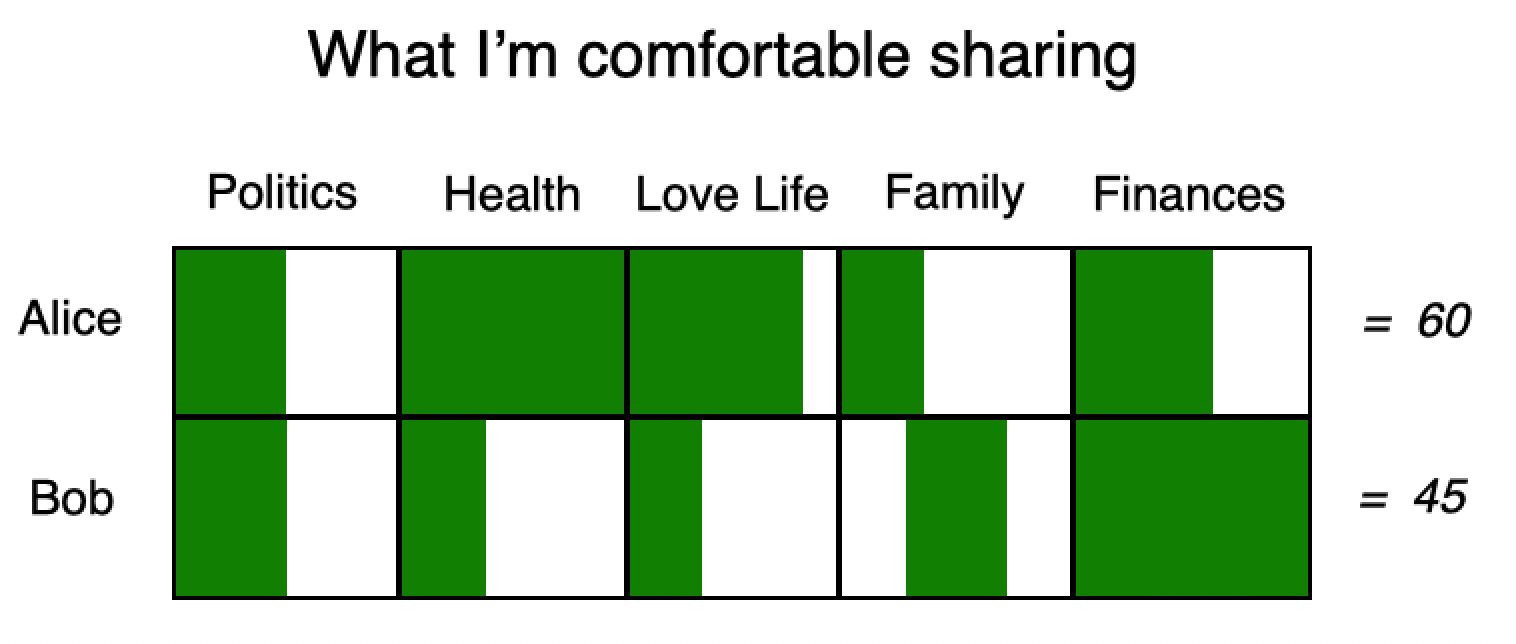

Comfortability Doesn’t Inherently Order Topics

Comfortability is a rough measure of the amount of personal information someone is willing to share with someone. However, this doesn’t mean that the topics are automatically ordered in terms of the scale. More precisely, you can share different areas of your life with different people, and just because you have a higher comfortability value with Alice than Bob doesn’t mean that you would tell everything you would to Bob to Alice. You could theoretically be willing to share everything about yourself with at least “someone”, even if you’d only share a small portion with each individual person. Therefore it’s not entirely accurate to say a certain topic has a value of 40, for example; maybe you’d share it with one friend who you’re at a 30 with, but not with another who you’re at a 50 with.

Sensitivity Decreases Comfortability

A large part of our relationships with others involves our opinions of them and topics they have strong opinions on. If someone is really sensitive, then you can never really get that close to them, as you must censor your opinions around them. This is particularly true if those opinions are about “them”.

If someone is insecure or too sensitive, you can’t tell them about their flaws or mistakes without compromising the relationship or facing retaliation. If a husband can’t tell his wife that she has a drinking problem, or a wife can’t tell her husband that he needs to lose weight, they must not actually be that close; they feel obligated to hide information from each other.

We can extend this past just our opinions of others. Some people are sensitive about their kids, their partners, their friends, politics, religion, health, race issues, gender issues, or any number of other topics. If someone can’t take the heat when I say something negative about their kids, friends, political views, religion, etc. then I must necessarily hide these parts of my beliefs from them if I want to maintain a good relationship with them.

Of course, sometimes we must make it clear that boundaries exist and we are not comfortable with certain views. For example, it’s entirely reasonable to be “sensitive” to Nazi-esque views and ideals and reject anyone with them. However, we must be aware this is a trade-off: if a Nazi sympathizer knows this about you, they might hide their true colors, and you’ll forever be in the dark about that. If you accept everyone and have the self-esteem and self-control to acknowledge any criticism directed at you, then anyone could open up to you. As such you’ll have the greatest amount of information available to work with.

Comfortability Asymmetry

Earlier I mentioned that two people could have a mutual comfortability of 50 between them. However, there’s no reason that two people can’t have different values for their relationship. For example, maybe one person is inherently far more trusting or generally less embarrassed than the other, resulting in a higher comfortability value. Or, perhaps one person has much more power than the other in the relationship, meaning they can comfortably express more things. While this is a valid concern, comfortability values are certainly highly correlated, so by knowing one person is at a 40, we can generally assume the other is likely much closer to 40 than 10 or 70. Furthermore, it’s also much cleaner to use single comfortability values to characterize a relationship — how clunky it would be to say 40/50 or 25/20 all the time?

Comfortability Applies to Everyone, Not Just Friends and Romance

To characterize the scale, I mostly talked about friends and romantic relationships. However, you could really characterize every relationship with it, although for some types of relationships it might be a bit tricky. For example, a teenager going through tough times might be really close to their parents and share plenty (and vice versa), but still hide their experimental drug usage from them. In this case, there is a high comfortability level between the teenager and their parents, but obviously, as the drug usage is being hidden, this level is capped.

A particularly asymmetric relationship could be that of a therapist and their patient, someone dealing with severe trauma. To resolve their issues, the patient must disclose extremely personal information and opinions that could be extremely difficult to acknowledge or very damaging to their existing and future relationships to the therapist. As a result, the patient must build a high level of comfortability with the therapist, but this need not be reciprocated fully in the other direction.

Comfortability is Perhaps Better Defined On Possible Experience

While harder to reason about, it is probably better to think of comfortability not in terms of just how much someone would share of what they’ve already experienced, but instead of how much they would share of what they could experience.

As an example, take Alice, a 25 year old who’s lived an extremely comfortable and uneventful life thus far. She grew up in a solidly middle-class suburban environment with two loving and happily married parents, and has a steady job giving her a comfortable (no pun intended) lifestyle. She has experienced nothing traumatic in her life, has no serious mental or physical health disorders, and is generally happy and satisfied with her life.

Now consider Bob, a 25 year old who grew up in extreme poverty in a war-torn country, whose immediate family all died horrifically a few years ago. Bob also struggles with severe depression and was abused as a child (this could go on and on.) In this case, Bob has actually experienced far more “personal” things in his life than Alice has, in the sense of being difficult to share. If very little of what Alice has experienced is difficult to share, we should not therefore assign her relationships relatively high comfortability levels.

We can try to combat this asymmetry by defining comfortability in terms of possible experience. In other words, comfortability can be thought of as the combination of all things you’d be willing to share with someone, if they actually happened to you. This is a bit unsatisfying though, as what does possible experience really refer to here? I’m never going to grow up in a war-torn country, so that isn’t a possible experience for me. This is impossible to define in a satisfying, precise way.

Ultimately, it’s clear that this comfortability scale can’t really be defined that precisely in terms of either prior or possible experience. I think the solution here is to be aware of both of these shortcomings, and try to use the framework to express general concepts, without worrying too much about exactly what everything means.

Multi-Person Comfortability

I’m assuming we can roughly define a comfortability level (or more precisely, a pair of comfortability values) between every pair of people. In groups of multiple people, it must be that your “group comfortability” corresponds to the amount of personal information you’re willing to share with every single person in the group. For example, if my best friend and I are talking with a minor acquaintance of ours, we’ll likely only express things at a level of around 10 or 20 instead of the 50 or so we normally would.

We can extend this idea to gossip and talking behind someone’s back. If you’re talking to someone known to be poor at keeping secrets, you’re likely going to have a lower comfortability level with them than you otherwise would. In essence, if Alice is planning on telling Bob and Chris what I tell her, then I might as well be talking to Alice, Bob and Chris at the same time. As a result, I necessarily have to reduce my comfortability level with Alice, as whenever I talk to her, I can assume that I’m effectively talking to a larger group of people with comfortability levels I cannot control.

Why Can’t You Share Everything With Someone?

Again, in discussing this I’m assuming the people involved have working filters on their speech and are sane. While I cannot characterize all human relationships, I feel it’s practically impossible for someone to be willing to share everything with someone else. Even if someone has lived a relatively mundane life with nothing notably embarrassing to share, we must keep in mind that the comfortability scale also deals with the realm of possible experience.

While there are numerous types of human relationships that can result in extreme closeness, I’ll just argue for this in the realm of romantic relationships as an example. We could imagine similar arguments for other relationships, like lifelong friends.

Imagine a long-time married couple who have lived almost their entire adult lives together and are as close to a model of lifelong partners that any couple could be. They are fully committed to each other and very satisfied with their relationship. I find it hard to believe that they’d be willing to share everything with each other. How confident are you that they would be willing to share the following sentiments with each other, roughly increasing in seriousness, assuming they were verifiably true, despite the closeness of their relationship?

- Alice was in love with Bob’s best friend 50 years ago, but settled for him because he rejected her and she wanted company (though Alice grew to love Bob over time)

- Bob secretly had a long-time affair with the coworker Alice had always been jealous of

- Alice cheated on Bob for many years and you Bob is not the father of their children

- Alice’s parents/children didn’t die accidentally — Bob couldn’t stand them and poisoned them himself

- Their daughter killed herself because Bob sexually abused her for years and threatened to kill her if she told anyone

- Bob had secretly been a pedophile for his whole life and has abused hundreds of children during his life, many of whom he killed, including one of their own.

Ouch — those hurt even to write, and I hope nobody quotes me out of context on them. Personally, I’d put the first part of the list very roughly around 70, and the last point around 95 or so. I don’t think any of them necessarily contradict the original premise of a close, loving couple; it’s just that one person (or maybe both) had some serious skeletons in the closet.

In any case, we could attempt to extend these statements into further moral depravity, but how many couples would even be willing to share all of the above? Remember, we have to deal with the realm of possible experience here. If everything about you is sharable, this doesn’t imply you can achieve perfect comfortability with someone; maybe you just haven’t been through anything sensitive enough to distinguish between the higher levels of comfortability.

You might think you’d share everything with your partner, but if a magician secretly transformed you into a pedophile unable to stop yourself from abusing children (including your own), do you think you could tell them what you’ve become? While such magicians (hopefully) don’t exist, if you’d hide that from your partner, then it follows that you aren’t perfectly close to them.

Now if you think two sane people could reasonably share all the above (and more) with each other, then you might know some interesting people, or maybe you’re thinking of two extremely mentally ill sociopaths, which I am not sure I’d count as sane. I cannot believe at this point in my life that two sane, normal people could actually achieve this.*

Of course, this is impossible to test and thus mostly a theoretical nit-picking, but that is my general argument for capping the scale around 90. I could perhaps see some people reaching a bit higher, but I think in general two people aren’t ever going to admit anything at the level of the second-to-last bullet point, except in very special circumstances.**

* Of course, someone who has actually done the last bullet point is very far from normal. However, I mean normal here more in the sense of being generally sane (not necessarily good, but sane) and capable of forming meaningful relationships. Perhaps it could be argued that nothing above the 80 — or 90, or 95 — level could possibly be done by a “normal” person, but I don’t think such an objection holds or even adds value.

** As stated before, and as I will argue in a future article, I believe comfort is inversely related to the power someone has on you. So, in the absence of power, we could achieve maximum comfort, e.g. with two inmates with no chance of ever escaping prison or harming each other. However, such fringe cases are not relevant to the vast majority of human interpersonal relationships that concern us.

Is 100 Even Achievable With Yourself?

Setting 100 to be everything you know about yourself seems pretty reasonable, but I think it’s reasonable to argue that many people already aren’t comfortable with everything about themselves. For example, perhaps some PTSD sufferers won’t allow themselves to, or are actually incapable of, facing some of their past experiences or actions, much less being able to share them with others.

We could thus define 100 as everything that someone could possibly acknowledge about themselves, and that everyone has a cap (perhaps 100, perhaps less) governing the things they’re actually willing to confront themselves on. However, I don’t know how useful acknowledging this detail is in practice, as if someone can’t acknowledge something themselves, it’s pretty useless to think about when talking about comfortability with others.

Comfortability Itself is a Sensitive Topic

To tell someone how comfortable you are with them is to explicitly show them a boundary on the extent of your relationship. Of course, everyone knows that all relationships differ in closeness. However, if you have a good friend for instance, by letting them know what value you assign them, you are explicitly letting them know that you are aware of an explicit range of topics you don’t feel comfortable sharing with them. Saying this explicitly gives a cap on the closeness of a relationship at a moment in time.

Of course, if you are dealing with a sensitive person, you will be incentivized to exaggerate your closeness to them. Such a person might be offended in your perceived shallowness of the relationship. Hence more so than just telling them a comfortability value, explicitly telling them the true value may require a high enough level of comfortability.

Further Extensions

I will reference the Comfortability Scale in future writings, as I find it a useful tool for analyzing interpersonal relationships. The concept is still in its infancy, so I am very open to feedback on further refining it.

Read Comfort, Trust, and Power next